DevOps with Kubernetes and VSTS: Part 1

If you’ve read my blog before, you’ll probably know that I am huge fan of Docker and containers. When was the last time you installed software onto bare metal? Other than your laptop, chances are you haven’t for a long time. Virtualization has transformed how we think about resources in the datacenter, greatly increasing the density and utilization of resources. The next evolution in density is containers - just what VMs are to physical servers, containers are to VMs. Soon, almost no-one will work against VMs anymore - we’ll all be in containers. At least, that’s the potential.

However, as cool as containers are for packaging up apps, there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how to actually run containers in production. Creating a single container is a cool and satisfying experience for a developer, but how do you run a cluster and scale containers? How do you monitor your containers? How do you manage faults? This is where we enter the world of container orchestration.

This post will cover the local development experience with Kubernetes and minikube. Part 2 covers the CI/CD pipeline to a Kubernetes cluster in Azure.

Orchestrator Wars

There are three popular container orchestration systems - Mesos, Kubernetes and Docker Swarm. I don’t want to go into a debate on which one you should go with (yet) - but they’re all conceptually similar. They all work off configuration as code for spinning up lots of containers across lots of nodes. Kubernetes does have a couple features that I think are killer for DevOps: ConfigMaps, Secrets and namespaces.

In short, namespaces allow you to segregate logical environments in the same cluster - the canonical example is a DEV namespace where you can run small copies of your PROD environment for testing. You could also use namespaces for different security contexts or multi-tenancy. ConfigMaps (and Secrets) allow you to store configuration outside of your containers - which means you can have the same image running in various contexts without having to bake environment-specific code into the images themselves.

Kubernetes Workflow and Pipeline

In this post, I want to look at how you would develop with Kubernetes in mind. We’ll start by looking at the developer workflow and then move on to how the DevOps pipeline looks in the next post. Fortunately, having MiniKube (a one-node Kubernetes cluster that runs in a VM) means that you can develop against a fully features cluster on your laptop! That means you can take advantage of cluster features (like ConfigMaps) without having to be connected to a production cluster.

So what would the developer workflow look like? Something like this:

- Develop code

- Build image from Dockerfile or docker-compose files

- Run service in MiniKube (which spins up containers from the images you just built)

It turns out that Visual Studio 2017 (and/or VS Code), Docker and MiniKube make this a really smooth experience.

Eventually you’re going to move to the DevOps pipeline - starting with a build. The build will take the source files and Dockerfiles and build images and push them to a private container registry. Then you’ll want to push configuration to a Kubernetes cluster to actually run/deploy the new images. It turns out that using Azure and VSTS makes this DevOps pipeline smooth as butter! That will be the subject of Part 2 - for now, we’ll concentrate on the developer workflow.

Setting up the Developer Environment

I’m going to focus on a Windows setup, but the same setup would apply to Mac or Linux environments as well. To set up a local development environment, you need to install the following:

You can follow the links and run the installs. I had a bit of trouble with MiniKube on HyperV - by default, MiniKube start (the command that creates the MiniKube VM) just grabs the first HyperV virtual network it finds. I had a couple, and the one that MiniKube grabbed was an internal network, which caused MiniKube to fail. I created a new virtual network called minikube in the HyperV console and made sure it was an external network. I then used the following command to create the MiniKube VM:

c:

cd \

minikube start --vm-driver hyperv --hyperv-virtual-switch minikube

Note: I had to cd to c:\ - if I did not, MiniKube failed to create the VM.

My external network if connected to my WiFi. That means when I join a new network, my minikube VM gets a new IP. Instead of having to update the kubeconfig each time, I just added a hosts entry in my hosts file (c:\windows\system32\drivers\etc\hosts on Windows) using “<IP> kubernetes”, where IP is the IP address of the minikube VM - obtained by running “minikube ip”. To update the kubeconfig, run this command: kubectl config set-cluster minikube --server= https://kubernetes:8443 --certificate-authority=c:/users/<user>/.minikube/ca.crt

where <user> is your username, so that the cert points to the ca.crt file generated into your .minikube directory.

Now if you join a new network, you just update the IP in the hosts file and your kubectl commands will still work. The certificate is generated for a hostname “kubernetes” so you have to use that name.

If everything is working, then you should get a neat response to “kubectl get nodes”:

PS:\> kubectl get nodes

NAME STATUS AGE VERSION

minikube Ready 11m v1.6.4

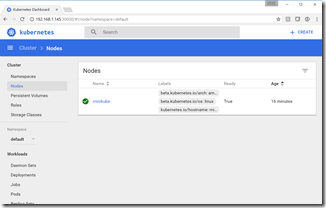

To open the Kubernetes UI, just enter “minikube dashboard” and a browser will launch:

Finally, to “re-use” the minikube docker context, run the following command: & minikube docker-env | Invoke-Expression

Now you are sharing the minikube docker socket. Running “docker ps” will return a few running containers - these are the underlying Kubernetes system containers. It also means you can create images here that the minikube cluster can run.

You now have a 1-node cluster, ready for development!

Get Some Code

I recently blogged about Aurelia development with Azure and VSTS. Since I already had a couple of .NET Core sites, I thought I would see if I could get them running in a Kubernetes cluster. Clone this repo and checkout the docker branch. I’ve added some files to the repo to support both building the Docker images as well as specifying Kubernetes configuration. Let’s take a look.

The docker-compose.yml file specifies a composite application made up of two images: api and frontend:

version: '2'

services:

api:

image: api

build:

context: ./API

dockerfile: Dockerfile

frontend:

image: frontend

build:

context: ./frontend

dockerfile: Dockerfile

The Dockerfile for each service is straightforward: start from the ASP.NET Core 1.1 image, copy the application files into the container, expose port 80 and run “dotnet app.dll” (frontend.dll and api.dll for each site respectively) as the entry point for each container:

FROM microsoft/aspnetcore:1.1

ARG source

WORKDIR /app

EXPOSE 80

COPY ${source:-obj/Docker/publish} .

ENTRYPOINT ["dotnet", "API.dll"]

To build the images, we need to dotnet restore, build and publish. Then we can build the images. Once we have images, we can configure a Kubernetes service to run the images in our minikube cluster.

Building the Images

The easiest way to get the images built is to use Visual Studio, set the docker-compose project as the startup project and run. That will build the images for you. But if you’re not using Visual Studio, then you can build the images by running the following commands from the root of the repo:

cd API

dotnet restore

dotnet build

dotnet publish -o obj/Docker/publish

cd ../frontend

dotnet restore

dotnet build

dotnet publish -o obj/Docker/publish

cd ..

docker-compose -f docker-compose.yml build

Now if you run “docker images” you’ll see the minikube containers as well as images for the frontend and the api:

Declaring the Services - Configuration as Code

We can now define the services that we want to run in the cluster. One of the things I love about Kubernetes is that it pushes you to declare the environment you want rather than running a script. This declarative model is far better than an imperative model, and we can see that with the rise of Chef, Puppet and PowerShell DSC. Kubernetes allows us to specify the services we want exposed as well as how to deploy them. We can define various Kubernetes objects using a simple yaml file. We’re going to declare two services: an api service and a frontend service. Usually, the backend services won’t be exposed outside the cluster, but since the demo code we’re deploying is a single page app (SPA), we need to expose the api outside the cluster.

The services are rarely going to change - they specify what services are available in the cluster. However, the underlying containers (or in Kubernetes speak, pods) that make up the service will change. They’ll change as they are updated and they’ll change as we scale out and then back in. To manage the containers that “make up” the service, we use a construct known as a Deployment. Since the service and deployment are fairly tightly coupled, I’ve placed them into the same file, so that we have a frontend service/deployment file (k8s/app-demo-frontend-minikube.yml) and an api service/deployment file (k8s/app-demo-backend-minikube.yml). The service and deployment definitions could live separately too if you want. Let’s take a look at the app-demo-backend.yml file:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: demo-backend-service

labels:

app: demo

spec:

selector:

app: demo

tier: backend

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

nodePort: 30081

type: NodePort

---

apiVersion: apps/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: demo-backend-deployment

spec:

replicas: 2

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: demo

tier: backend

spec:

containers:

- name: backend

image: api

ports:

- containerPort: 80

imagePullPolicy: Never

Notes:

- Lines 1 - 15 declare the service

- Line 4 specified the service name

- Line 8 - 10 specify the selector for this service. Any pod that has the labels app=demo and tier=frontend will be load balanced for this service. As requests come into the cluster that target this service, the service will know how to route the traffic to its underlying pods. This makes adding, removing or updating pods easy since all we have to do is modify the selector. The service will get a static IP, but the underlying pods will get dynamic IPs that will change as they move through their lifecycle. However, this is transparent to us, since we just target the service and all is good.

- Line 14 - we want this service exposed on port 30081 (mapping to port 80 on the pods, as specified in line 13)

- Line 15 - the type NodePort specifies that we want Kubernetes to give the service a port on the same IP as the cluster. For “real” clusters (in a cloud provider like Azure) we would change this to get an IP from the cloud host.

- Lines 17 - 34 declare the Deployment that will ensure that there are containers (pods) to do the work for the service. If a pod dies, the Deployment will automatically start a new one. This is the construct that ensures the service is up and running.

- Line 22 specifies that we want 2 instances of the container for this service at all times

- Lines 26 and 27 are important: they must match the selector labels from the service

- Line 30 specifies the name of the container within the pod (in this case we only have a single container in this pod anyway, which is generally what you want to do)

- Line 31 specifies the name of the image to run - this is the same name as we specified in the docker-compose file for the backend image

- Line 33 exposes port 80 on this container to the cluster

- Line 34 specifies that we never want Kubernetes to pull the image since we’re going to build the images into the minikube docker context. In a production cluster, we’ll want to specify other policies so that the cluster can get updated images from a container registry (we’ll see that in Part 2).

The frontend definition for the frontend service is very similar - except there’s also some “magic” for configuration. Let’s take a quick look:

spec:

containers:

- name: frontend

image: frontend

ports:

- containerPort: 80

env:

- name: "ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT"

value: "Production"

volumeMounts:

- name: config-volume

mountPath: /app/wwwroot/config/

imagePullPolicy: Never

volumes:

- name: config-volume

configMap:

name: demo-app-frontend-config

Notes:

- Line 30: name the container in the pod

- Line 31: specify the name of the image for this container - matching the name in the docker-compose file

- Lines 34 - 36: an example of how to specify environment variables for a service

- Lines 37 - 39: this is a reference to a volume mount (specified lower down) for mounting a config file, telling Kuberenetes where in the container file system to mount the file. In this case, Kubernetes will mount the volume with name “config-volume” to the path /app/wwwroot/config inside the container.

- Lines 41 - 44: this specifies a volume - in this case a configMap volume to use for the configuration (more on this just below). Here we tell Kubernetes to create a volume called config-volume (referred to by the container volumeMount) and to base the data for the volume off a configMap with the name demo-app-frontend-config

Handling Configuration

We now have a couple of container images and can start running them in minikube. However, before we start that, let’s take a moment to think a little about configuration. If you’ve ever heard me speak or read my blog, you’ll know that I am a huge proponent of “build once, deploy many times”. This is a core principle of good DevOps. It’s no different when you consider Kubernetes and containers. However, to achieve that you’ll have to make sure you have a way to handle configuration outside of your compiled bits - hence mechanisms like configuration files. If you’re deploying to IIS or Azure App Services, you can simply use the web.config (or for DotNet Core the appsettings.json file) and just specify different values for different environments. However, how do you do that with containers? The entire app is self-contained in the container image, so you can’t have different versions of the config file - otherwise you’ll need different versions of the container and you’ll be violating the build once principle.

Fortunately, we can use volume mounts (a container concept) in conjunction with secrets and/or configMaps (a Kubernetes concept). In essence, we can specify configMaps (which are essentially key-value pairs) or secrets (which are masked or hidden key-value pairs) in Kubernetes and then just mount them via volume mounts into containers. This is really powerful, since the pod definition stays the same, but if we have a different configMap we get a different configuration! We’ll see how this works when we deploy to a cloud cluster and use namespaces to separate dev and production environments.

The configMaps can also be specified using configuration as code. Here’s the configuration for our configMap:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: demo-app-frontend-config

labels:

app: demo

tier: frontend

data:

config.json: |

{

"api": {

"baseUri": "http://kubernetes:30081/api"

}

}

Notes:

- Line 2: we specify that this is a configMap definition

- Line 4: the name we can refer to this map by

- Line 9: we’re specifying this map using a “file format” - the name of the file is “config.json”

- Lines 10 - 14: the contents of the config file

Aside: Static Files Symlink Issue

I did have one issue when mounting the config file using configMaps: inside the container the volume mount to /app/www/config/config.json ends up being a symlink. I got the idea of using a configMap in the container from this excellent post by Anthony Chu, in which he mounts an application.json file that the Startup.cs file can consume. Apparently he didn’t have any issues with the symlink in the Startup file. However, in the case of my demo frontend app, I am using a config file that is consumed by the SPA app - and that means, since it’s on the client side, the config file needs to be served from the DotNet Core app, just like the html or js files. No problem - we’ve already got a UseStaticFiles call in Startup, so that should just serve the file, right? Unfortunately, it doesn’t. At least, it only serves the first few bytes of the file.

I took a couple of days to figure this out - there’s a conversation on Github you can read if you’re interested. In short, the symlink length is not the length of the file, but the length of the path to the file. The StaticFiles middleware reads FileInfo.Length bytes when the file is requested, but since the length isn’t the full length of the file, only the first few bytes were being returned. I was able to create a FileProvider that worked around the issue.

Running the Images in Kubernetes

To run the services we just created in minikube, we can just use kubectl to apply the configurations. Here’s the list of commands (the highlighted lines):

PS:\> cd k8s

PS:\> kubectl apply -f .\app-demo-frontend-config.yml

configmap "demo-app-frontend-config" created

PS:\> kubectl apply -f .\app-demo-backend-minikube.yml

service "demo-backend-service" created

deployment "demo-backend-deployment" created

PS:\> kubectl apply -f .\app-demo-frontend-minikube.yml

service "demo-frontend-service" created

deployment "demo-frontend-deployment" created

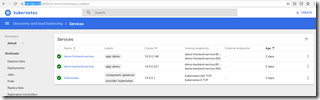

And now we have some services! You can open the minikube dashboard by running “minikube dashboard” and check that the services are green:

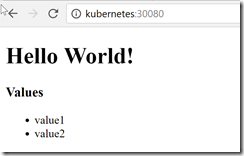

And you can browse to the frontend service by navigating to http://kubernetes:30080:

The list (value1 and value2) are values coming back from the API service - so the frontend is able to reach the backend service in minikube successfully!

Updating the Containers or Containers

If you update your code, you’re going to need to rebuild the container(s). If you update the config, you’ll have to re-run the “kubectl apply” command to update the configMap. Then, since we don’t need high-availability in dev, we can just delete the running pods and let the replication set restart them - this time with updated config and/or code. Of course in production we won’t do this - I’ll show you how to do rolling updates in the next post when we do CI/CD to a Kubernetes cluster.

For dev though, I get the pods, delete them all and then watch Kubernetes magically re-start the containers again (with new IDs) and voila - updated containers.

PS:> kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

demo-backend-deployment-951716883-fhf90 1/1 Running 0 28m

demo-backend-deployment-951716883-pw1r2 1/1 Running 0 28m

demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-bfzhv 1/1 Running 0 14s

demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-q4f9l 1/1 Running 0 24s

PS:> kubectl delete pods demo-backend-deployment-951716883-fhf90 demo

-backend-deployment-951716883-pw1r2 demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-bfzhv demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-q4f9l

pod "demo-backend-deployment-951716883-fhf90" deleted

pod "demo-backend-deployment-951716883-pw1r2" deleted

pod "demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-bfzhv" deleted

pod "demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-q4f9l" deleted

PS:> kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

demo-backend-deployment-951716883-4dsl4 1/1 Running 0 3m

demo-backend-deployment-951716883-n6z4f 1/1 Running 0 3m

demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-j2scj 1/1 Running 0 3m

demo-frontend-deployment-477968527-wh8x0 1/1 Running 0 3m

Note how the pods get updated IDs - since they’re not the same pods! If we go to the frontend now, we’ll see updated code.

Conclusion

I am really impressed with Kubernetes and how it encourages infrastructure as code. It’s fairly easy to get a cluster running locally on your laptop using minikube, which means you can develop against a like-for-like environment that matched prod - which is always a good idea. You get to take advantage of secrets and configMaps, just like production containers will use. All in all this is a great way to do development, putting good practices into place right from the start of the development process.

Happy sailing! (Get it? Kubernetes = helmsman)