Modernizing Source Control - Migrating to Git

I remember when I first learned about Git circa 2012. I was skeptical - you can change history? What kind of source control system let you change history? However, it seemed to have huge momentum and so I started learning how to use it. Once you get over the initial learning curve - and there is one when you switch from centralized version control systems like Team Foundation Version Control (TFVC) or Subversion - I started to see the beauty of Git. And now I believe that teams can benefit enormously if they migrate to Git. I believe that so strongly that I spoke about this very topic at VSLive! in Orlando earlier this month.

In this post I want to detail why I think migrating to Git makes sense, common objections I hear, and some common ways you can migrate to Git. Migrating to Git make business sense as well as technical sense - so I’ll call out business value-adds along the way. I’ll primarily be talking about migrating from TFVC, but similar principles apply if you’re migrating from other centralized source control systems.

Why Git?

There are several reasons why I think Git is essential for modern teams:

- Branches are cheap

- Merging is better

- Code review is baked in via Pull Request

- Better offline workflow

Cheap Branches

The primary reason I love Git is that branches are cheap. We’ll get to the technical reasons why this important next - but the main business benefit of cheap branches lies in the ability to easily isolate (and later merge) development streams. That should be exciting since it means that small changes can be completed, merged and deployed without having to be held hostage by larger, longer-running changes. Delays cost, so anything that eliminates delays is good!

In centralized version control, a branch is a complete copy of the source - so typically teams keep the number of branches small. With Git, branches are essentially pointers, so creating branches is cheap. This means teams can create a lot of branches. Why does this make a difference anyway? The idea of a branch is to isolate code changes. Typical TFVC branching strategy is “DEV-MAIN-PROD”. This is an attempt to isolate code in development (DEV) from code that’s being tested (MAIN) and code that’s running in production (PROD). That seems at first glance to be exactly what we want branches for - however, there’s a catch: what if we have two or ten or twenty features in development? I coach teams to check in early, check in often - but that means that at times the code that’s checked in will be unstable. Teams expect this at in the DEV branch. In fact, there’s a term for how stable a branch is: hardness. The DEV branch is considered “soft” since it’s not always stable - while PROD is supposed to be “hard” - that is, stable. But this branching strategy is flawed in that it isolates code at too coarse a level. What we really want is to isolate more granularly - especially if we want to deploy smaller features when they’re complete without having to wait for larger features to be ready for deployment.

Git allows teams to create a branch per feature - also commonly referred to as topic branching. You don’t want to do this when each branch is an entire copy of the code-base - but since Git branches are pointers, we can create branches liberally. By using a good naming convention and periodically cleaning branches that are stale (that haven’t been updated for long periods) teams can get very good at isolating changes, and that makes their entire application lifecycle more resilient and more agile and minimize costly delays.

Better Merging

Merge debt can also be costly - the further away two branches diverge, the more costly and risky merging them becomes. Again, thinking in “business terms”, this means you can move faster, with better quality - and what business doesn’t want that?

Let’s imaging you have 20 features in flight on a single DEV branch, and you somehow manage to coordinate a merge when all the features are ready to go, you’ll probably spend a lot of time working through the merge since there are so many changes. Also, features that are completed quickly are forced to wait until the slowest feature is complete - which is a lot of waste. Or teams decide to merge anyway, knowing that they’re merging incomplete code.

Also, when a file changes in a Git repo, Git records the entire file, not just the diffs (like TFVC). This means that merging between arbitrary branches works. With TFVC, branches have to be related to merge - or you could try a dreaded “baseless merge”, which is very error-prone. Even though Git stores the entire file for a change, it does so very efficiently, but because of this merging is far easier for the Git.

Empirically I find that Git teams have fewer merge conflicts and merge issues than TFVC teams. Let’s now imaging that we are using Git and have 20 features in flight - and 3 are ready to be deployed, but we want to test them. If we want to test them individually, no problem - we do a build off the branch which is master (the stable code) plus the branch changes. We can queue 3 builds and test each feature in isolation. We can also merge any branch into any of the others (something you can’t easily do in unrelated branches in TFVC), so we can also test them together and make sure that there are no breaking changes in the merge - even before we merge each branch to master! This let’s teams deploy features much more rapidly and frequently, eliminating waste along the way.

Code Reviews

One of GitHub’s engineers introduced the concept of Pull Requests (PRs) and it’s since become ubiquitous in the Git world - even though you don’t typically do PRs in your local Git repo. The PR lets developers advertise that their code is ready to be merged. Policies (and reviews) can be built around the PR so that only quality code is merged into master. PRs are dynamic - so if I am the reviewer and comment on some code that a developer has submitted in a PR, the developer can fix the code and I can see the changes “live” in the PR. In contrast, TFVC lets you submit a Code Review work item (only through the Visual Studio IDE) and if the code needs to be changed, a new Code Review needs to be created. The whole code review process is clunky and laborious. However, I find PRs to be unobtrusive - they let us check code quickly, respond and adapt, and finally merge in a really natural manner. The Azure DevOps PR interface is fantastic - and if you add branch policies (available in Azure DevOps) you can enforce links to work items, comment resolution, build verification and even external system checks before a PR is merged. This lets teams “shift left” and build quality into their process in a natural, powerful and unobtrusive manner.

Better Offline

Git is a distributed version control system - it’s designed to be used locally and synchronized to a central repo for sharing changes. As such, disconnected workflows are natural and powerful - and since cloning a repository gets the entire history of the repo from day 0, and I can branch and merge locally, the disconnected experience is excellent. TFVC used to require connection to the server to do most source control operations - with local workspaces (circa 2013) some source control operations can be performed offline, but you still need to be connected to the server to branch and merge.

Common Objections

There are four common objections I often hear to migrating to Git:

- I can overwrite history

- I have large files

- I have a very large repo

- I don’t want to use GitHub

- There’s a steep learning curve

Overwriting History

Git technically does allow you to overwrite history - but (as we know from Spiderman) with great power comes great responsibility! If your teams are careful, they should never have to overwrite history. And if you’re synchronizing to Azure DevOps you can also add a security rule that prevents developers from overwriting history (you need the “Force Push” permission enabled to actually sync a repo that’s had rewritten history). The point is that every source control system works best when the developers using it understand how it works and which conventions work. While you can’t overwrite history with TFVC, you can still overwrite code and do other painful things. In my experience, very few teams have managed to actually overwrite history.

Large Files

Git works best with repos that are small and that do not contain large files (or binaries). Every time you (or your build machines) clone the repo, they get the entire repo with all its history from Day 0. This is great for most situations, but can be frustrating if you have large files. Binary files are even worse since Git just can’t optimize how they are stored. That’s why Git LFS was created - this lets you separate large files out of your repos and still have all the benefits of versioning and comparing. Also, if you’re used to storing compiled binaries in your source repos - stop! Use Azure Artifacts or some other package management tool to store binaries you have source code for. However, teams that have large files (like 3D models or other assets) you can use Git LFS to keep your code repo slim and trim.

Large Repos

This used to be a blocker - but fortunately the engineers at Microsoft have been on a multi-year journey to convert all of Microsoft’s source code to Git. The Windows team has a repo that’s over 300GB in size, and they use Git for source control! How? They invented Virtual File System (VFS) for Git. VFS for Git is a client plugin that lets Git think it has the entire repo - but only fetches files from the upstream repo when a file is touched. This means you can clone your giant repo in a few seconds, and only when you touch files does Git fetch them down locally. In this way, the Windows team is able to use Git even for their giant repo.

Git? GitHub?

There is a lot of confusion about Git vs GitHub. Git is the distributed source control system created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 for the Linux kernel. If you create a repo, you have a fully functioning Git repo on your local machine. However, to share that code, you need to pick a central place that developers can use to synchronize their repos - so if I want your changes, you’d push your changes to the central repo, and I’d pull them from there. We’re still both working totally disconnected - but we’re able to share our code via this push/pull model. GitHub is a cloud service for hosting these sorts of centralized repos - made famous mostly because it’s free for open source projects (so you can host unlimited public repos). You don’t have to use GitHub to use Git - though it’s pretty much the de-facto platform for open source code. They do offer private repos too - but if you’re an enterprise, you may want to consider Azure Repos since you get unlimited private repos on Azure Repos. You can also create Git repos in Team Foundation Server (TFS) from TFS 2015 to TFS 2019 (now renamed to Azure DevOps Server).

Learning Curve

There is a learning curve - if you’ve never used source control before you’re probably better off when learning Git. I’ve found that users of centralized source control (TFVC or SubVersion) battle initially to make the mental shift especially around branches and synchronizing. Once developers grok how Git branches work and get over the fact that they have to commit and then push, they have all the basics they need to be successful in Git. I’ve never once had a team convert to Git and then decide they want to switch back to centralized source control!

Git and Microservices

Microservices are all the rage today - I won’t go into details in this post about why - there’s plenty of material available explaining why the industry is trending towards microservices. Conway’s Law tells us that the structure of our architecture is strongly influenced by the structure of our organization. The inverse, Conway’s Inverse Maneuver, postulates that you can influence the structure of an organization by the way you architect your systems! If you’ve been battling to get to microservices within your organization, consider migrating to Git and decomposing your giant central repo into smaller Git repos as a method of influencing your architecture. Perhaps someone has already come up with a “law” for this - if not, I’ll coin “Colin’s Repo Law” which states that the way that you structure your source code will influence everything else in the DevOps lifecycle - builds, releases, testing and so on. So be sure to structure your source code and repos with the end goal in mind!

Migrating to Git

Before we get to how to migrate, we have to address the issue of history. When teams migrate source control systems, they always ask about history. I push back a bit and inform teams that their old source control system isn’t going away, so you don’t lose history. For a small period of time, you may have two places to check for history - but most teams don’t check history further out than the last month regularly. Some teams may have compliance or regulatory burdens, but these are generally the exception. Don’t let the fear of “losing history” prevent you from modernizing your source control!

Monorepo or Multirepo?

The other consideration we have to make is monorepo or multirepo? A monorepo is a Git repo that contains all the code for a system (or even organization). Generally, Git repos should be small - my rule of thumb is the repo boundary should be the deployment boundary. If you always deploy three services at the same time (because they’re tightly coupled) you may want to put the code for all three services into a single repo. Then again, you may want to split them and start moving to decouple them - only you can decide what’s going to be correct.

If you decide to split your repo into multiple Git repos, you’re going to have to consider what to do with shared code. In TFVC, you have shared code in the same repo as the applications, so you generally just have project references. However, if you split out the app code and the common code, you are going to have to have a way to consume the compiled shared code in the application code - that’s a good use case for package management. Depending on your source control structure, the complexity of your system and your team culture, this may not be easy to do - in that case you may decide to just convert to a monorepo instead of a set of smaller repos.

The Azure DevOps team decided to use a monorepo even though their system is composed of around 40 microservices. They did this because the source code for Azure DevOps (which Microsoft hosts themselves as a SaaS offering) is the same source code that is used for the on-premises out-of-the-box Azure DevOps Server (previously TFS). Their CI builds are triggered off paths in the repo instead of triggering a build for every component every time the repo is changed. If you decide to use a monorepo, make sure your CI system is capable of doing this - and make sure you organize your source code into appropriate folders for managing your builds!

Migrating

So how can you migrate to Git? There are at least three ways:

- Tip migration

- Azure DevOps single branch import

- Git-tfs import

Tip Migration

Most teams I work with wish they could reorganize their source control structure - typically the structure the team is using today was set up by a well-meaning developer a decade ago but it’s not really optimal. Migrating to Git could be a good opportunity to restructure your repo. In this case, it probably doesn’t make sense to migrate history anyway, since you’re going to restructure the code (or break the code into multiple repos). The process is simple: create an empty Git repo (or multiple empty repos), then get-latest from TFS and copy/reorganize the code into the empty Git repos. Then just commit and push and you’re there! Of course if you have shared code you need to create builds of the shared code to publish to a package feed and then consume those packages in downstream applications, but the Git part is really simple.

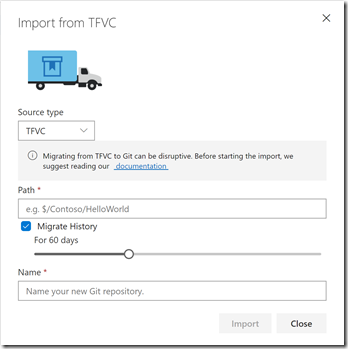

Single Branch Import

If you’re on TFVC and you’re in Azure DevOps (aka VSTS) then you have the option of a simple single-branch import. Just click on “Import repository” from the Azure Repos top level drop-down menu to pop open the dialog. Then enter the path to the branch you’re migrating (yes, you can only choose one branch) and if you want history or not (up to 180 days). Then add in a name for the repo and let ‘er rip!

There are some limitation here: a single branch and only 180 days of history. However, if you only care about one branch and you’re already in Azure DevOps, then this is a no-brainer migration method.

Git-tfs

What if you need to migrate more than a single branch and retain branch relationships? Or you’re going to ignore my advice and insist on dragging all your history with you? In that case, you’re going to have to use Git-tfs. This is an open-source project that is build to synchronize Git and TFVC repos. But you can use it to do a once-off migration using git tfs clone

. Git-tfs has the advantage that it can migrate multiple branches and will preserve the relationships so that you can merge branches in Git after you migrate. Be warned that it can take a while to do this conversion - especially for large repos or repos with long history. You can easily dry-run the migration locally, iron out any issues and then do it for real. There’s lots of flexibility with this tool, so I highly recommend it.

If you’re on Subversion, then you can use Git svn to import your Subversion repo in a similar manner to using Git-tfs.

Conclusion

Modernizing source control to Git has high business value - most notably the ability to effectively isolate code changes, minimize merge debt and integrate unobtrusive code reviews which can improve quality. Add to this the broad user-base for Git and you have a tool that is both powerful and pervasive. With Azure DevOps, you can also add “enterprise” features like branch policies, easily manage large binaries and even large repos - so there’s really no reason not to migrate. Migrating to Git will cause some short-term pain in terms of learning curve, but the long term benefits are well worth it.

Happy source controlling!