Container DevOps: Beyond Build (Part 5) - Prometheus Operator

Series:

- Part 1: Intro

- Part 2: Traefik Basics

- Part 3: Canary Testing

- Part 4: Telemetry with Prometheus

- Part 5: Prometheus Operator (this post)

In part 4 of this series I showed how I created a metrics endpoint using Prometheus in my .NET Core application. While not perfect for business telemetry, Prometheus is a standard for performance metrics. But that only exposes an endpoint for metrics - it doesn’t do any visualization. In this post I’ll go over how I used Prometheus Operator in a k8s cluster to easily scrape metrics from services and then in the next post I’ll cover how I configured Grafana to visualize those metrics - first by hand and then using infrastructure-as-code so that I can audit and/or recreate my entire monitoring environment from source code.

Container DevOps Recap: The Importance of Monitoring

Monitoring is often the black sheep of DevOps - it’s not stressed very much. I think that’s partly because monitoring is hard - and often, contextual. Boards for work management and pipelines for build and release are generally more generic in concept and most teams starting with DevOps seem to start with these tools. However, Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment should be complimented by Continuous Monitoring.

One of my DevOps heroes (and by luck of life, friend) Donovan Brown coined the quintessential definition of DevOps a few years ago: DevOps is the union of people, products and process to enable continuous delivery of value to end users. I’ve heard some folks criticize this definition for its lack of mention of monitoring among other things - but I think that a lot of Donovan’s definition is implied (at least should be implied) in the phrase “value”.

Most teams think of value in terms of features: I’d like to propose that monitoring as a mechanism of keeping systems stable, resilient and responsive is just as important as delivering features. So in a very real sense, his definition implies monitoring. I’ve also heard Donovan state that it doesn’t matter how good your code is, if it’s not in the hands of your users, it doesn’t deliver value. In the same vein, it doesn’t matter how good your features are: if you can’t monitor for errors, scale or usage then you’re missing delivering value for your users.

In a world of microservices and Kubernetes, the need for solid monitoring is paramount, and more difficult. Monoliths may be hard to change, but they are by and large easy to monitor. Microservices increase the complexity of monitoring, but there are some techniques that teams can use to manage the complexity.

Prometheus Operator

In the last post I showed how I exposed Prometheus metrics from my services. Imagine you have 10 or 15 services - how do you monitor each one? Exposing metrics via Prometheus is all well and good, but how do you aggregate and visualize the metrics that are being produced? The first step is Prometheus itself - or the Prometheus instance (to be disambiguated by the Prometheus metrics endpoint that containers or services expose).

If you were manually setting up an instance of Prometheus, you would have to install the pods and services in a k8s cluster as well as configure Prometheus to tell it where to scrape metrics from. This manual process is complex, error prone and time-consuming: enter the Prometheus Operator.

Installing the Prometheus operator (and instance) itself is simple thanks to the official helm chart. This also (optionally) includes endpoints for monitoring the health of your k8s cluster components via kube-prometheus. It also installs AlertManager for automating alerts - I haven’t played with this though.

K8s Operators are a mechanism for deploying applications to a k8s cluster - but these applications tend to be “smarter” than regular k8s applications in that they can hook into the k8s lifecycle. Point-in-case: scraping telemetry for a newly deployed service. The Prometheus Operator will automagically update the Prometheus configuration via the k8s API when you declare that a new service has Prometheus endpoints. This is done via a custom resource definition (CRD) that is created by the Prometheus helm chart: ServiceMonitors. When you create a service that exposes a Prometheus metrics endpoint, you simply declare a ServiceMonitor alongside your service to dynamically update Prometheus and let it know that you have a new service that can be scraped: including which port and how frequently to scrape.

Configuring Prometheus Operator

The helm chart for Prometheus Operator is a beautiful thing: it means you can install and configure a Prometheus instance, the Prometheus Operator and kube-prometheus (for monitoring cluster components) with a couple lines of script. Here’s how I do this in my release pipeline:

helm repo add coreos https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/coreos-charts/stable/

helm upgrade --install prometheus-operator coreos/prometheus-operator --namespace monitoring

helm upgrade --install kube-prometheus coreos/kube-prometheus --namespace monitoring

Notes:

- Line 1: Add the CoreOS repo for the stable Prometheus operator charts

- Line 2: Install (or upgrade) the Prometheus operator into a namespace called “monitoring”

- Line 3: Install the kube-prometheus components - this gives me cluster monitoring

These commands are also idempotent so I can run them every time without worrying about current state - I always end up with the correct config. Querying the services in the monitoring namespace we see the following:

alertmanager-operated ClusterIP None <none> 9093/TCP,6783/TCP 60d

kube-prometheus ClusterIP 10.0.240.33 <none> 9090/TCP 60d

kube-prometheus-alertmanager ClusterIP 10.0.168.1 <none> 9093/TCP 60d

kube-prometheus-exporter-kube-state ClusterIP 10.0.176.16 <none> 80/TCP 60d

kube-prometheus-exporter-node ClusterIP 10.0.251.145 <none> 9100/TCP 60d

prometheus-operated ClusterIP None <none> 9090/TCP 60d

</none></none></none></none></none></none>

Configuring ServiceMonitors

Now that we have a Prometheus instance (and the Operator) configured we can examine how to tell the Operator that there’s a new service to monitor. Fortunately, now that we have the ServiceMonitor CRD, it’s pretty straight-forward: we just declare a ServiceMonitor resource alongside our service! Let’s take a look at one:

apiVersion: monitoring.coreos.com/v1

kind: ServiceMonitor

metadata:

name: website-monitor

namespace: monitoring

labels:

prometheus: kube-prometheus

tier: website

spec:

jobLabel: app

selector:

matchLabels:

release: pu-dev-website

system: PartsUnlimited

app: partsunlimited-website

namespaceSelector:

any: true

endpoints:

- port: http

path: /site/metrics

interval: 15s

Notes:

- Lines 1-2: We’re using the custom resource ServiceMonitor

- Line 7: We’re using a label to ringfence this Service - we’ve configured the Prometheus service to look for ServiceMonitors with this label

- Lines 11-15: This ServiceMonitor applies to all services with these matching labels

- Lines 18-21: We configure the port (a named port in this case) and path for the Prometheus endpoint, as well as what frequency to scrape the metrics

When we create this resource, the Operator picks up the creation of the ServiceMonitor resource via the k8s API and configures the Prometheus server to now scrape metrics from our service(s).

PromQL

Now that we have some metrics going into Prometheus, we have the ability to query the metrics. We start by port-forwarding the Prometheus instance so that we can securely access it (you can also expose the instance publicly if you want to): kubectl port-forward svc/kube-prometheus -n monitoring 9090:9090

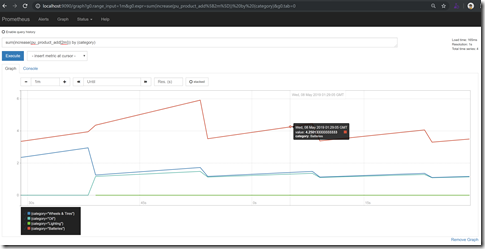

Then we can browse to http://localhost:9090/graph and see the Prometheus instance. We can then query metrics using PromQL - a language to query, aggregate and visualize metrics. For example, to see the rate of increase in sales by category for the last 2 minutes, we can write sum(increase(pu_product_add[2m])) by (category)

And then we can visualize it by clicking on the graph button:

This is a proxy for how well sales are doing on our site by category. And while this is certainly great, it’s far better to visualize Prometheus metrics in Grafana dashboards - which we can do using the PromQL queries. But that’s a topic for a future post in this series!

Conclusion

Prometheus and the Prometheus Operator make configuring metric aggregation really easy. It’s declarative, dynamic and intuitive. This makes it a really good framework for monitoring services within a k8s cluster. In the next post I’ll show how you can hook Grafana up to the Prometheus server in order to make visualizations of the telemetry. Until then:

Happy monitoring!