Container DevOps Beyond Build: Part 2 - Traefik

- Works In My Orchestrator ™

- Ops Criteria

- Configuring Traefik Controllers

- Configuring Ingresses

- Conclusion

Series:

- Part 1: Intro

- Part 2: Traefik (this post)

- Part 3: Canary Testing

- Part 4: Telemetry with Prometheus

- Part 5: Prometheus Operator

In Part 1 of this series, I outlined some of my goals and some of the thinking around what I think Container DevOps is - it’s far more than just being able to build and run a container or two. Beyond just automating builds, you have to think about how you’re going to release. Zero downtime and canary testing, resiliency and monitoring are all table stakes - but while I understand how to do that using Azure Web Apps, I hadn’t done a lot of these for containerized applications. After working for a couple of months on a Kubernetes (k8s) version of .NET Core PartsUnlimited, I have some thoughts to share on how I managed to put these practices into place.

When thinking about running containers in production, you have to think about the end to end journey, starting at building images right through deployment and into monitoring and tracing. I’m a firm believer in building quality into the pipeline early, so automated builds should unit test (with code coverage), do static analysis and finally package applications. In “traditional web” builds, the packaging usually means a zip or WebDeploy package or NPM package or even just a drop of files. When building container images, you’re inevitably using a Dockerfile - which makes compiling and packaging simple, but leaves a lot to be desired when you want to test code or do static analysis, package scanning and other quality controls. I’ve already blogged about how I was able to add unit testing and code coverage to a multi-stage Dockerfile - I just got SonarQube working too, so that’s another post in the works.

Works In My Orchestrator ™

However, assume that we have an image in our container registry that we want to deploy. You’ve probably run that image on your local machine to make sure it at least starts up and exposes the right ports, so it works on your machine. Bonus points if you ran it in a development Kubernetes cluster! But now how do you deploy this new container to a production cluster? If you just use k8s Deployment rolling update strategy. you’ll get zero-downtime for free, since k8s brings up the new container and replaces the existing ones only when the new ones are ready (assuming you have good liveness and readiness probes defined). But how do you test the new version for only a small percentage of users? Or secure traffic to that service? Or if you’re deploying multiple services (microservices anyone?) how do you monitor traffic flow in the service mesh? Or cut out “bad” services so that they don’t crash your entire system?

With these questions in mind, I started to investigate how one does these sorts of things with deployments to k8s. The rest of this post is about my experiences.

Ops Criteria

Here’s the list of criteria I had in mind to cover - and I’ll evaluate three tools using these criteria:

- Internal and External Routing - I want to be able to define how traffic “external” traffic (traffic originating outside the cluster) and “internal” traffic (traffic originating and terminating within the cluster) is routed between services.

- Secure Communication - I want communication to endpoints to be secure - especially external traffic.

- Traffic Shifting - I want to be able to shift traffic between services - especially for canary testing.

- Resiliency - I want to be able to throttle connections or implement circuit breaking to keep my app as a whole resilient.

- Tracing - I want to be able to see what’s going on across my entire application.

I explored three tools: Istio, Linkerd and Traefik. I’ll evaluate each tool against the five criteria above.

Spoiler: Traefik won the race!

Disclaimer: some of these tools do more than these five things, so this isn’t a wholistic showdown between these tools - it’s a showdown over these five criteria only. Also, Traefik is essentially a reverse proxy on steroids, while Istio and Linkerd are service meshes - so you may need some functionality of a service mesh that Traefik can’t provide.

Internal and External Routing

All three tools are capable of routing traffic. Istio and Linkerd both inject sidecar proxies to your containers. I like this approach since you can abstract away the communication/traffic/monitoring from your application code. This seemed to be promising, and while I was able to get some of what I wanted using both Istio and Linkerd, both had some challenges. Firstly, Istio is huge, rich and complicated. It has a lot of Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) - more than k8s itself in fact! So while it worked for routing like I wanted, it seemed very heavy. Linkerd worked for external routing, but due to limitations in the current implementation, I couldn’t get it working to route internal traffic.

Let’s say you have a website and make a code change - you want to test that in production - but only to a small percentage of users. With Azure App Services, you can use Traffic Manager and deployment slots for this kind of canary testing. Let’s say you get the “external” routing working - most clients connecting to your website get the original version, while a small percentage get the new version. This is what I mean by “external” traffic. But what if you have a microservice architecture and your website code is calling internal services which call other internal services? Surely you want to be able to do the same sort of traffic shifting - that’s “internal” routing - routing traffic internally within the cluster. Linkerd couldn’t do that for me - mostly due to incompatibility between the control plane and the sidecars, I think.

Traefik did this easily via Ingress Controllers (abstractions native to k8s). I set up two controllers - one to handle “external” traffic and one to handle “internal” traffic - and it worked beautifully. More on this later.

Secure Communication

I didn’t explore this topic too deeply with either Istio or Linkerd, but Traefik made securing external endpoints with certificates via LetsEncrypt really easy. I tried to get secure communication for my internal services, but I was trying with a self-signed cert and I think that’s what prevented it from working. I’m sure that you could just as easily add this capability into internal traffic using Traefik if you really needed to. We’ll see this later too - but using a static IP and DNS on an Azure Load Balancer, I was able to get secure external endpoints with very little fuss!

Traffic Shifting

If you’ve got routing, then it follows that you should be able to shift traffic to different services (or more likely, different versions of the same service). I got this working in Istio (see my Github repo and mardown on how I did this here) and Linkerd only worked for external traffic. With Istio you shift by defining a VirtualService - it’s an Istio CRD that’s a love-child between a Service and an Ingress. With Linkerd, traffic rules are specified using dtabs - it’s a cool idea (abstracting routes) but the implementation was horrible to work with - trying to learn the obscure format and debug it was not great.

By far the biggest problem with both Istio and Linkerd is that their network routing doesn’t understand readiness or liveness probes since the work via their sidecar containers. This becomes a problem when you’re deploying a new version of a service using a rolling upgrade - as soon as the service is created, Istio or Linkerd start sending traffic to the endpoint, irrespective of the readiness of that deployment. You can probably work around this, but I found that I didn’t have to if I used Traefik.

Traefik lets you declaratively specify weight rules to shift traffic using simple annotations on a standard Ingress resource. It’s clean and intuitive when you see it. The traffic shifting also obeys readiness/liveness probes, so you don’t start getting traffic routed to services/deployments that are not yet ready. Very cool!

Resiliency

First, there’s a lot of things to discuss in terms of resiliency - for this post I’m just looking at features like zero-downtime deployment, circuit breaking and request limiting. Istio and Linkerd both have control planes for defining circuit breakers and request limiting - Traefik let’s you define these as annotations. Again, this comparison is a little apples-for-oranges since Traefik is “just” a reverse proxy, while Istio and Linkerd are service meshes. However, the ease of declaration of these features is so simple in Traefik, it’s compelling. Also, since Traefik builds “over” rolling updates in Deployments, you get zero-downtime deployment for free. If you’re using Istio, you have to be careful about your deployments since you can get traffic to services that are not yet ready.

Tracing

Traefik offloads monitoring to Prometheus and the helm chart has hooks into DataDog, Zipkin or Jaeger for tracing. For my experiments, I deployed Prometheus and Grafana for tracing and monitoring. Both Istio and Linkerd have control planes that include tracing - including mesh visualization - which can be really useful for tracing microservices since you can see traffic flow within the mesh. With Traefik, you need additional tools.

Configuring Traefik Controllers

So now you know some of the reasons that I like Traefik - but how do you actually deploy it? There are a couple components to Traefik: the Ingress Controller (think of this as a proxy) and then ingresses themselves - these can be defined at the application level and specify how the controller should direct traffic to the services within the cluster. There’s another component (conceptually) and that is the ingress class: you can have multiple Traefik ingress controllers, and if you do, you need to specify a class for each controller. When you create an ingress, you also annotate that ingress to specify which controller should handle its traffic - you’re essentially carving the ingress space into multiple partitions, each handled by a different controller.

For the controller, there are some other “under the hood” components such as secrets, config maps, deployments and services - but all of that can be easily deployed and managed via the Traefik Helm chart. You can quite easily deploy Traefik with a lot of default settings using --set

from the command line, but I found it started getting unwieldy. I therefore downloaded the default values.yml file and customized some of the values. When deploying Traefik, I simply pass in my customized values.yml file to specify my settings.

For my experiments I wanted two types of controller: an “external” controller that was accessible from the world and included SSL. I also wanted an “internal” controller that was not accessible outside of the cluster that I could use to do internal routing. I use Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS), so the code for this series assumes that.

Let’s take a look at the values file of the “internal” controller:

image: traefik

imageTag: 1.7.7

serviceType: NodePort

kubernetes:

ingressClass: "dev-traefik-internal"

ssl:

enabled: false

acme:

enabled: false

dashboard:

enabled: true

domain: traefik-internal-ui.aks

rbac:

enabled: true

metrics:

prometheus:

enabled: true

restrictAccess: false

datadog:

enabled: false

statsd:

enabled: false

Notes:

- Lines 1-3: The image it “traefik” and we want the 1.7.7 version. Since this is just internal, we only need a NodePort service (I tried ClusterIP, but that didn’t work).

- Line 6: we want this ingress controller to watch and manage traffic for Ingresses that have this class as their annotation. This is how we have multiple Traefik controllers within a cluster. I prepend the class with the namespace (dev) too!

- Lines 7,8: Since this is an internal ingress, we don’t need SSL. I tried to get this working, but suspect I had issues with the certs. If you need internal SSL, this is where you’d set it.

- Lines 10,11: This is for generating a cert via LetsEncrypt. Not needed for our internal traffic.

- Lines 14,15: Enable the dashboard. I accessed via port-forwarding, so the domain isn’t critical.

- Lines 16,17: RBAC is enabled.

- Lines 18-25: tracing options - I just enabled Prometheus.

Let’s now compare the values file for the “external” controller:

image: traefik

imageTag: 1.7.7

serviceType: LoadBalancer

loadBalancerIP: "101.22.98.189"

kubernetes:

ingressClass: "dev-traefik-external"

ssl:

enabled: true

enforced: true

permanentRedirect: true

upstream: false

insecureSkipVerify: false

generateTLS: false

acme:

enabled: true

email: myemail@somewhere.com

onHostRule: true

staging: false

logging: false

domains:

enabled: true

domainsList:

- main: "mycoolaks.westus.cloudapp.azure.com"

challengeType: tls-alpn-01

persistence:

enabled: true

dashboard:

enabled: true

domain: traefik-external-ui.aks

rbac:

enabled: true

metrics:

prometheus:

enabled: true

restrictAccess: false

datadog:

enabled: false

statsd:

enabled: false

tracing:

enabled: false

Most of the file is the same, but here are the differences:

- Line 4: We specify the static IP we want the LoadBalancer to use - I have code that pre-creates this static IP (with DNS name) in Azure before I execute this script.

- Line 7: We specify a different class to divide the “ingress space”.

- Lines 8-14: These are the LetsEncrypt settings, including the domain name, challenge type and persistence to store the cert settings.

Now that we have the controllers (internal and external) deployed, we can deploy “native” k8s services and ingresses (with the correct annotations) and everything Will Just Work ™.

Configuring Ingresses

Assuming you have the following service:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: dev-partsunlimitedwebsite

namespace: dev

spec:

type: NodePort

selector:

app: partsunlimited-website

function: web

ports:

- name: http

port: 80

Then you can define the following ingress:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

annotations:

kubernetes.io/ingress.class: dev-traefik-external

labels:

app: partsunlimited-website

function: web

name: dev-website-ingress

namespace: dev

spec:

rules:

- host: mycoolaks.westus.cloudapp.azure.com

http:

paths:

- backend:

serviceName: dev-partsunlimitedwebsite

servicePort: http

path: /site

Notes:

- Line 2: This resource is of type “Ingress”

- Lines 4,5: We define the class - this ties this Ingress to the controller with this class - for our case, this is the “external” Traefik controller

- Lines 12-18: We’re specifying how the Ingress Controller (Traefik in this case) should route traffic. This is the simplest configuration - take requests coming to the host “mycoolaks.westus.cloudapp.azure.com” and route them to the “dev-partsunlimitedwebsite” service onto the “http” port (port 80 if you look at the service definition above).

- Line 19: We can use the Traefik controller to front multiple services - using the path helps to route effectively.

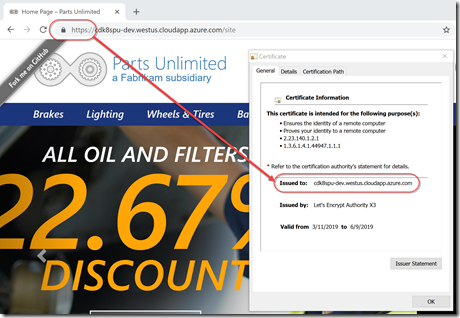

When you access the service, you’ll see the secure padlock in the browser window and be able to see details for the valid cert:

The best thing is I didn’t have to generate the cert myself - Traefik did it all for me.

There’s more that we can configure on the Ingress - including the traffic shifting for canary or A/B testing. We can also annotate the service to include circuit-breaking - but I’ll save that for another post now that I’ve laid out the foundation for traffic management using Traefik.

Conclusion

Container DevOps requires thinking about how traffic is going to flow in your cluster - and while there are many tools for doing this, I like the combination of simplicity and power you get with Traefik. There’s still a lot more to explore in Container DevOps - hopefully this post gives you some insight into my thoughts.

Happy container-ing!